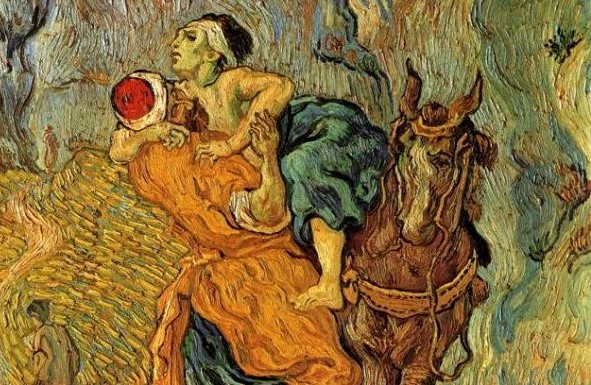

"Walk worthy of the vocation in which you are called, with all humility and mildness, with patience, supporting on another in charity, careful to keep the unity of the Spirit in the bond of peace." Ephesians 4:1-3

Divine Intimacy tells us it is easy keep the bond of peace when we are truly humble, meek and patient. Such a soul is said to "bear everything with love, carefully trying to adapt itself to the feelings and desires of others, rather than asserting its own." However it also points out that this is very difficult here below because self love continually "asserts its rights" creating "continual clashes, the avoidance of which calls for much self-renunciation and much delicacy towards others."

Very often, the author points out, "the cause of division among good people is excessive self assertion: the desire to do things ones own way." He states certainly that, "there can be nothing so absolute in our ideas that it cannot give way to the ideas of others." If our ideas our good, others may also be good. They may be better. Therefore he says, "it is much wiser, more humble and charitable to accept the views of others and to try to reconcile our views to theirs."

He goes further to say, "We should be persuaded that all that disturbs, weakens, or worse still, destroys fraternal union, does not please God." He says this is so even when we are moved under the pretext of zeal. So long as it does not interfere with our fulfillment of duty or the law of God. Remember too, we are called to live out that law, not to loudly condemn all who do not. They will have their hour of reckoning. May God be merciful to us all in that regard.

The closing prayer reads in part:

"O Word, Son of God, You look with more complacency on one work done in fraternal union and charity than on a thousand done in discord;

one tiny little act, like the closing of an eye, performed in union and charity, pleases You more than if I were to suffer martyrdom in disunion and without charity.

You are the source of all peace."

From the Liturgy:

Where charity and love are, You are there also, O Lord!

Your love, O Christ, has united us in one body with a sincere heart.

Grant then that we may love one another with a sincere heart.

Keep far from us all quarrels and contentions;

grant that our hearts may always be united in You and do You dwell always in our midst.